Food safety is a critical concern in both domestic kitchens and commercial food production. One of the most persistent and widespread threats to food safety is microbiological contamination, which is the primary cause of food poisoning. Bacteria, viruses, and moulds can contaminate food through various means, leading to illness, hospitalisation, and, in severe cases, fatalities.

Understanding the risks associated with foodborne pathogens is essential for anyone handling food, whether at home or in a professional setting. While some bacteria are beneficial, others can cause food spoilage or pose serious health risks. In this article, we will explore the different types of bacteria, how they multiply, and the conditions that allow them to thrive. We will also discuss sources of contamination, the dangers of cross-contamination, and practical measures to prevent bacterial growth.

By following proper food safety guidelines, we can minimise the risks of foodborne illnesses and ensure that the food we prepare and consume is safe.

Microbiological contamination is the main source of food poisoning, which is arguably the most common and persistent food safety problem.

Food poisoning can be brought on by toxins being added to the food or by bacteria, viruses, or moulds getting into the food and spreading infections.

Table of Contents

Bacteria

We discovered that food poisoning is the biggest risk associated with handling food. The most common cause of this type of disease is bacterial exposure.

Bacteria are single-celled, microscopic organisms that live around the world and are present on and in nearly everything, including food and cooking utensils.

From the dirt beneath our feet to the human stomach, they can be found everywhere from the deepest oceans to the uppermost reaches of the skies. While some are dangerous in the wrong area, cause food to decay, or spread disease, the majority are benign and many are helpful to us.

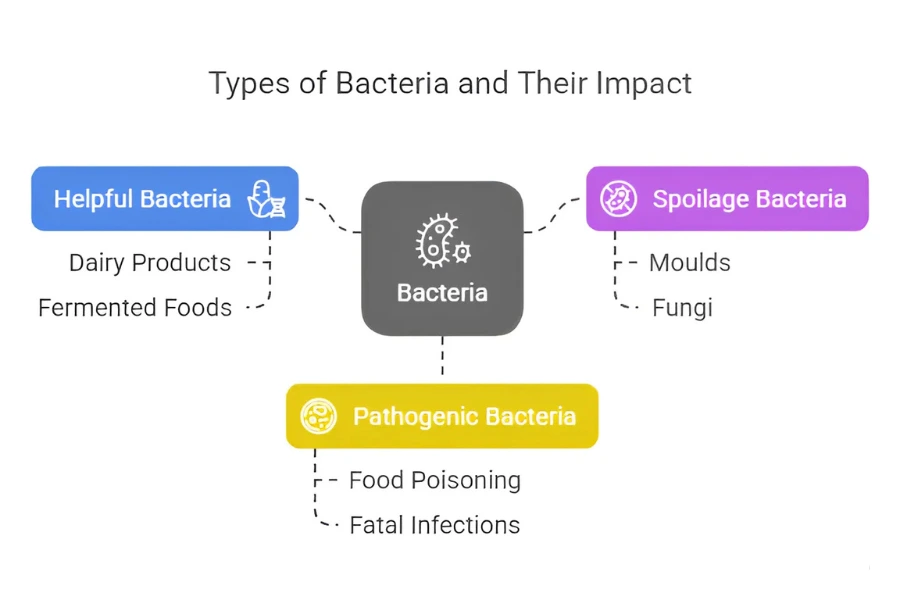

Types of Bacteria

There are three kinds of bacteria for our purposes:

- Helpful bacteria

- Spoilage bacteria

- Pathogenic bacteria

However, it is the last two which cause problems in food handling and production.

- As food breaks down, spoilage microorganisms cause it to smell “off,” turn discoloured, and otherwise become unappealing

- Disease and illness are caused by harmful germs.

Helpful Bacteria

Not all bacteria are bad; in fact, some beneficial bacteria are essential to our survival.

Dairy and fermented foods are the main sources of these. Foods that contain beneficial microorganisms include, for example:

- Live yoghurt (which includes probiotic bacteria)

- Sauerkraut (fermented cabbage preserved in saltwater)

- Tempeh (fermented soya bean extracts)

- Kimchee (Korean cabbage fermented in spices)

- Miso (fermented soya bean paste)

- Pickles

However, we now need to consider the kinds of bacteria that poison food.

“Beneficial bacteria in the gut help digest food, produce vitamins, and protect against harmful pathogens.”

— National Institutes of Health (NIH), Human Microbiome Project.

Spoilage Bacteria

In essence, food spoiling is the process by which food starts to break down and is typically obvious. Food that is spoilt will not taste good, so you should avoid eating it while it is spoilt.

Moulds, various fungi, viruses, and certain bacteria known as spoilage bacteria are among the organisms that eventually grow and multiply on any food items that are left untreated.

Though they make food inedible and unfit for human consumption, these aren’t always harmful.

“Spoilage bacteria break down food components, producing metabolites that alter smell, flavor, and appearance. Proper storage slows their growth, extending shelf life.”

— World Health Organization (WHO), specialized agency for Health.

Pathogenic Bacteria

Numerous important bacterial species are responsible for the very hazardous group of disorders known as “food poisoning.” These are known as pathogenic bacteria, and they can be especially harmful because there are sometimes no outward signs that they are present in food.

Although you constantly come into contact with thousands of different kinds of bacteria, it is the common yet dangerous ones that contaminate our food and water and can occasionally lead to fatal infections.

In the UK, there are over a million food poisoning episodes annually, leading to over 20,000 hospital hospitalisations and over 500 fatalities.

There are seven main categories of harmful bacteria that are commonly found in our food:

- Salmonella

- Clostridium perfringens

- Bacillus cereus

- Campylobacter

- Escherichia coli (E coli) 0157

- Listeria

- Staphylococcus aureus

“Not all bacteria are harmful, but pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella and E. coli can cause serious infections requiring medical intervention.”

— Mayo Clinic, is a private American academic medical center.

How Do Bacteria Multiply?

Despite being mobile organisms, bacteria divide in two to reproduce, grow, and multiply, which is extremely different from how animals do it.

A bacterium will multiply if its immediate surroundings contains enough nutrients, as well as the right amount of moisture and temperature. In a relatively short period of time, this will lead to a fast multiplication—some types of bacteria can double in number every 20 minutes!

This implies that in just eight hours, a single bacterium can multiply into almost 16 million.

It goes without saying that one of the most important aspects of any food handler’s duty is to prevent the conditions necessary for bacterial development from spreading and endangering people.

The conditions needed by bacteria to multiply are perhaps best remembered using the acronym F.A.T.T.O.M.

This stands for:

- Food

- Acidity

- Temperature

- Time

- Oxygen

- Moisture

What is FATTOM?

FATTOM is a simple tool used to remember six key factors that help bacteria grow on food. These factors are food, acidity, time, temperature, oxygen, and moisture. Each element contributes to how quickly harmful bacteria can spread, especially when personal hygiene practices are not followed properly.

FATTOM can be clarified by describing the ways in which each of these elements promotes the growth of bacteria:

Foods: high in protein that are warm and damp are especially conducive to the growth of germs.

Acidity: Since most bacteria cannot survive or develop in acidic environments, vinegar and lemon juice make excellent preservatives.

Temperature: the “Danger Zone,” which is between 4°C and 60°C, is the ideal temperature range for bacterial growth.

Time: Foods become more hazardous the longer they provide the circumstances for bacterial growth because they foster an environment that is more conducive to growth.

Oxygen: There are two types of bacteria that depend on the presence or absence of oxygen:

- Vacuum-sealed containers can stop aerobic germs from multiplying because they require oxygen to flourish.

- Anaerobic bacteria will contaminate food jars or cans that have been poorly treated since they can only grow when oxygen is absent.

Moisture: Because bacteria develop more quickly in damp environments, foods that are salted and dried are typically considered low-risk.

Sources and Vehicles of Bacterial Contamination

Bacteria can enter food in a variety of ways, but they can be broadly divided into three categories: direct, indirect, and passive cross-contamination.

Although cross-contamination will be covered in further depth below, passive contamination can occur in a number of ways:

- Food animals can carry diseases from their intestines or skins during slaughter, and faeces can cross across during evisceration.

- Salmonella can infect eggs, and poultry slaughtering equipment can spread infection from bird to bird.

- Bacteria in shellfish build up by filter-feeding in live molluscs; uncooked shellfish is especially dangerous.

- Raw fruits and vegetables may harbour soil microorganisms that have been contaminated by insects and other animals through urine and food contact.

- Since milk is the ideal medium for bacterial proliferation, it must be pasteurised in order to eradicate bacteria.

- Static and storage tank water should only be used for washing, not drinking; water must be appropriately treated to neutralise runoff from sewage, slurry, and soil.

Cross-contamination

There are two kinds of contamination:

- Indirect

- Direct

When harmful bacteria are transferred from a source to food through a vehicle, this is known as indirect contamination.

The following are examples of when this can occur:

- Using gloves or not washing your hands before handling food

- When working with raw meat and then cooked meat or vegetables, a chopping board or knife is not cleaned or sanitised.

- Those used for preparing raw food should be cleaned using the same dishcloth as those used for cooking.

Direct contamination occurs when the pathogen’s source comes into touch with food without a step in between.

Example of this can include:

- When the person handling the food sneezes or coughs on it

- When raw chicken is kept in a refrigerator over cooked chicken

- When cooked meat is kept next to or in the middle of fresh flesh

- When raw fish is kept atop veggies or salad

Bacteria and the Danger Zone

As we’ve seen, one among the elements that promotes bacterial development under FATTOM is temperature.

- The ‘Danger Zone’ between 4° to 60°C is where bacterial development is most fast; in fact, most bacteria cannot reproduce outside of this range.

- Our healthy body temperature of 37° C is located exactly in the centre of that rage, which may be our misfortune or evolution’s cunning. The majority of germs that cause human illness reproduce best at this temperature.

- Therefore, in order to avoid bacterial growth, food safety rules and protocols require that: Cold food be stored below 5°C and hot food be stored above 63°C.

Although storing cold food below 8°C is required by law, it is best practice to keep it below 5°C.

To eradicate microorganisms, all food, whether served hot or cold, must have been cooked through. In fact, undercooking might promote the growth and reproduction of bacteria.

This implies that food must be cooked for two minutes, and ideally longer, at 70°C (or above).

How to Prevent Bacterial Contamination

You can avoid cross-contamination and bacterial growth by adhering to the following guidelines:

- Equipment that has been cleansed and disinfected should be used to prepare raw and ready-to-eat food separately.

- It is necessary to carefully wash fresh vegetables in a separate wash basin.

- Never wash utensils in the sink where raw food is being prepared.

- Work surfaces and utensils should be cleaned or dried using single-use, disposable cloths.

- Both before and after handling raw food, you must properly wash your hands.

- Whenever feasible, food should be moved and placed using ladles, spoons, or tongs.

- Whenever feasible, gloves should be worn, and they should be changed after handling food.

- Hand washing should be done before donning protective gloves.

- Food should never be left standing in a warm or damp area.

- Make as little food as you can to avoid keeping it out of the refrigerator for too long.

Viruses

Although they are still minute, viruses are completely separate species from bacteria and are also the cause of some food diseases.

In essence, a virus is a parasite that reproduces inside the cells of other species to infect them and cause illnesses. However, they must be consumed in order to reproduce because they require a living cell to accomplish this.

Hepatitis A and norovirus are the two most common viral food-borne diseases. Both are easily contagious and can persist for extended lengths of time on work surfaces, light switches, and door handles.

Since both are prevalent in shellfish and other seafood, these items need to be validated as having been gathered from authorised sources.

Other than heating food properly, there isn’t much protection against viruses because they can withstand disinfectant resistance and bactericidal hand washes.

Moulds

Moulds are microscopic fungi that mostly consume dead plant or animal debris. Their even smaller spores, which can be spread by the air, water, or living things like flies, are how they are spread.

It is far more widespread than is typically thought, with thin roots that pierce the food’s surface. It is primarily noticeable as a green, blue, yellowish, or white surface dusting.

Not only is it ugly, but moulds release digestive enzymes that cause food to deteriorate and develop the telltale symptoms of spoiling or decomposition, like an unpleasant or mouldy odour, an unusually slimy look, and an odd colour.

Furthermore, certain types of mould can cause deadly mycotoxins, which are poisonous compounds that are introduced into food. These are usually consumed through wheat or other grains that have developed mould while being stored.

High Risk and Low Risk Foods

Understanding the difference between high and low risk foods is important for food safety. It helps reduce the chance of illness by guiding how we handle, store, and prepare various items.

High Risk Foods

‘High risk’ foods are those that are more likely to include bacteria, viruses, or moulds due to the environment required to promote their growth.

These foods are often ones that are prepared for consumption; some examples are as follows:

- Pre-cooked fish, poultry and meat, including ‘deli meats’

- Shellfish and other seafood

- Cheese, cream, fresh milk and other dairy products

- Stocks, gravies, sauces, chowders and soups

- Cooked pasta

- Cooked rice

- Unwashed leafy greens and salad

- Unwashed fruit

- Vegetable sprouts

Low Risk Foods

These are foods that are often dry or preserved and don’t require refrigeration or heating. As such, they do not offer a conducive environment for the growth of microorganisms.

The following are typical examples of such foods, which typically carry a “best before” or shelf-life date on their labels or packaging:

- Crisps and corn chips

- Crackers and breadsticks

- Packeted breakfast cereals

- Dried rice, pasta, quinoa and couscous

- Pastries, cakes and biscuits (without dairy-based cream or fillings)

- Sweets and other sugar-based confectionery

- Canned drinks

- Tinned food

- Cooking sauces in sealed jars

- Condiments including table sauces

Some of them fast turn into high-risk foods once they are opened and taken out of the refrigerator; they should be stored and eaten according to the instructions on the container.

Conclusion

Food safety isn’t just a responsibility—it’s a necessity. Every meal we prepare and consume carries the potential for contamination if proper precautions aren’t taken. While the world of bacteria, viruses, and moulds may seem invisible and overwhelming, the good news is that we have the knowledge and tools to keep them at bay.

By understanding how bacteria multiply, recognising high-risk foods, and practising good hygiene, we can significantly reduce the chances of foodborne illness. Simple actions—like storing food at the right temperature, avoiding cross-contamination, and cooking meals thoroughly—can make all the difference in preventing harmful pathogens from taking hold.

Ultimately, safe food handling isn’t just about following rules—it’s about protecting our health, our families, and everyone who shares our meals. So, the next time you step into the kitchen, remember: a little extra care can go a long way in keeping food safe and delicious!

FAQs

What is the definition of contamination?

Contamination refers to the presence of harmful or unwanted substances—such as chemicals, microbes, or pollutants—in an environment, food, water, or product, making it impure or unsafe. It can occur naturally (e.g., bacterial growth in food) or through human activities (e.g., industrial waste in rivers). Contamination compromises quality, safety, or usability, often requiring cleanup or prevention measures. For example, water contamination by heavy metals can harm health, while soil contamination affects agriculture. Unlike competitors’ vague definitions, this explanation clarifies types, sources, and impacts, ensuring practical understanding. Regular monitoring, strict regulations, and sustainable practices are key to preventing contamination and protecting ecosystems and human health.

What are the 3 types of food contamination?

The three main types of food contamination are biological, chemical, and physical. Biological contamination occurs when harmful microorganisms like bacteria (e.g., Salmonella), viruses, or molds contaminate food, often due to improper handling or cooking. Chemical contamination involves substances like pesticides, cleaning agents, or food additives accidentally entering food, posing health risks. Physical contamination happens when foreign objects, such as glass, hair, or metal fragments, end up in food during processing or preparation. Preventing these requires strict hygiene, proper storage, and regular equipment checks. Understanding these risks helps ensure food safety and protects consumers from illnesses.

How can we prevent food contamination?

To prevent food contamination, follow these key practices: Wash hands, utensils, and surfaces thoroughly before and after handling food. Store raw meat, poultry, and seafood separately to avoid cross-contamination. Cook foods to safe internal temperatures (e.g., 165°F for poultry). Refrigerate perishable items promptly at or below 40°F. Use clean, potable water for cooking and cleaning. Avoid consuming expired or visibly spoiled food. When shopping, choose frozen or refrigerated items last and check for intact packaging. Regularly sanitize kitchen areas, especially cutting boards and countertops. Educate yourself on safe food handling through resources like the FDA or CDC guidelines. By maintaining hygiene, proper storage, and safe cooking practices, you can significantly reduce the risk of foodborne illnesses.

What is food hygiene law?

Food hygiene law refers to the legal standards businesses must follow to ensure food is safe to eat. In the UK, the main legislation is the Food Safety Act 1990 and the Food Hygiene Regulations 2006. These laws require food businesses to handle, store, prepare, and serve food in a way that prevents contamination and protects public health. Key rules include maintaining clean premises, training staff in hygiene, ensuring proper temperature control, and preventing cross-contamination. Local authorities enforce these laws through inspections and can issue fines or close unsafe businesses. Compliance isn’t just about avoiding penalties—it’s essential for building trust, protecting customers, and running a successful food business. Understanding food hygiene law is crucial for anyone working in food handling or hospitality.

What is the Food Safety Act 1990?

The Food Safety Act 1990 is a key UK law ensuring food safety and consumer protection in England, Wales, and Scotland. It mandates that food businesses—restaurants, cafes, or factories—avoid adding or removing substances that could harm consumers, ensure food meets expected quality and substance, and label products accurately without misleading claims. Non-compliance risks fines up to £20,000 or imprisonment. The Act, enforced by local authorities and the Food Standards Agency, sets the framework for food hygiene and safety regulations, protecting public health by preventing foodborne illnesses. It applies to all stages of food handling, from production to sale, ensuring safe, high-quality food for consumers.

How do you treat food contamination?

To treat food contamination, first identify the source—bacterial (e.g., Salmonella), chemical (e.g., pesticides), or physical (e.g., glass). Discard contaminated food to prevent health risks like food poisoning. Clean and sanitize affected surfaces, utensils, and equipment using hot water and food-safe disinfectants. For minor contamination, cooking food to proper internal temperatures (e.g., 165°F for poultry) can kill bacteria, but this won’t neutralize chemical or physical hazards. Prevent cross-contamination by separating raw and cooked foods and using dedicated cutting boards. Wash hands thoroughly before handling food. If contamination is widespread, consult local health authorities for guidance. Regular training on food safety and adherence to HACCP principles can prevent future issues. Always store food at safe temperatures (below 40°F for perishables) to limit bacterial growth.

- Available Courses

- Animal care10

- Design28

- Training9

- Accounting & Finance Primary49

- Teaching & Academics Primary37

- Teaching23

- Quality Licence Scheme Endorsed175

- Law10

- IT & Software229

- Job Ready Programme52

- Charity & Non-Profit Courses28

- HR & Leadership4

- Administration & Office Skills4

- Mandatory Training36

- Regulated Courses4

- AI & Data Literacy24

- Health and Social Care290

- Personal Development1623

- Food Hygiene119

- Safeguarding80

- Employability288

- First Aid73

- Business Skills294

- Management425

- Child Psychology40

- Health and Safety532

- Hospitality28

- Electronics31

- Construction62

- Career Bundles201

- Marketing39

- Healthcare172

Food Hygiene

Food Hygiene Health & Safety

Health & Safety Safeguarding

Safeguarding First Aid

First Aid Business Skills

Business Skills Personal Development

Personal Development